EU Law, encompassing the legal framework and principles governing the EU, is a unique legal system that operates alongside national laws within the EU member states. Although it is an optional module you can choose to study in Year 2, it is one of the foundation modules for entry into bar training. It is also partially assessed in the form of retained EU law in the SQE for intending solicitors. Here is a summary of the topics covered in this module:

EU Treaties and Their Significance: The EU treaties are legal agreements that define the functioning, objectives, and structure of the EU. They establish the legal framework within which the EU operates, outlining its institutions, decision-making processes, policies, and the rights and obligations of its member states. The EU treaties are of significant importance as they provide the basis for the EU's integration and cooperation among member states.

History and Reforms of the Founding Treaties: The EU's founding treaties trace back to the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951, which aimed to prevent future wars by integrating the coal and steel industries of its member states. The Treaty of Rome in 1957 then created the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM). These treaties laid the foundation for the common market and cooperation in the peaceful use of nuclear energy. Over the years, the EU treaties have undergone several reforms to adapt to the evolving needs and challenges of the Union. The Single European Act (SEA) of 1986 aimed to complete the internal market, while the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 created the European Union and introduced the pillars of the EU: the European Communities, the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), and Justice and Home Affairs (JHA). The subsequent treaties, such as the Amsterdam Treaty (1999), Nice Treaty (2001), and Lisbon Treaty (2007), brought further reforms, including the expansion of qualified majority voting, strengthening of the European Parliament, and enhanced cooperation.

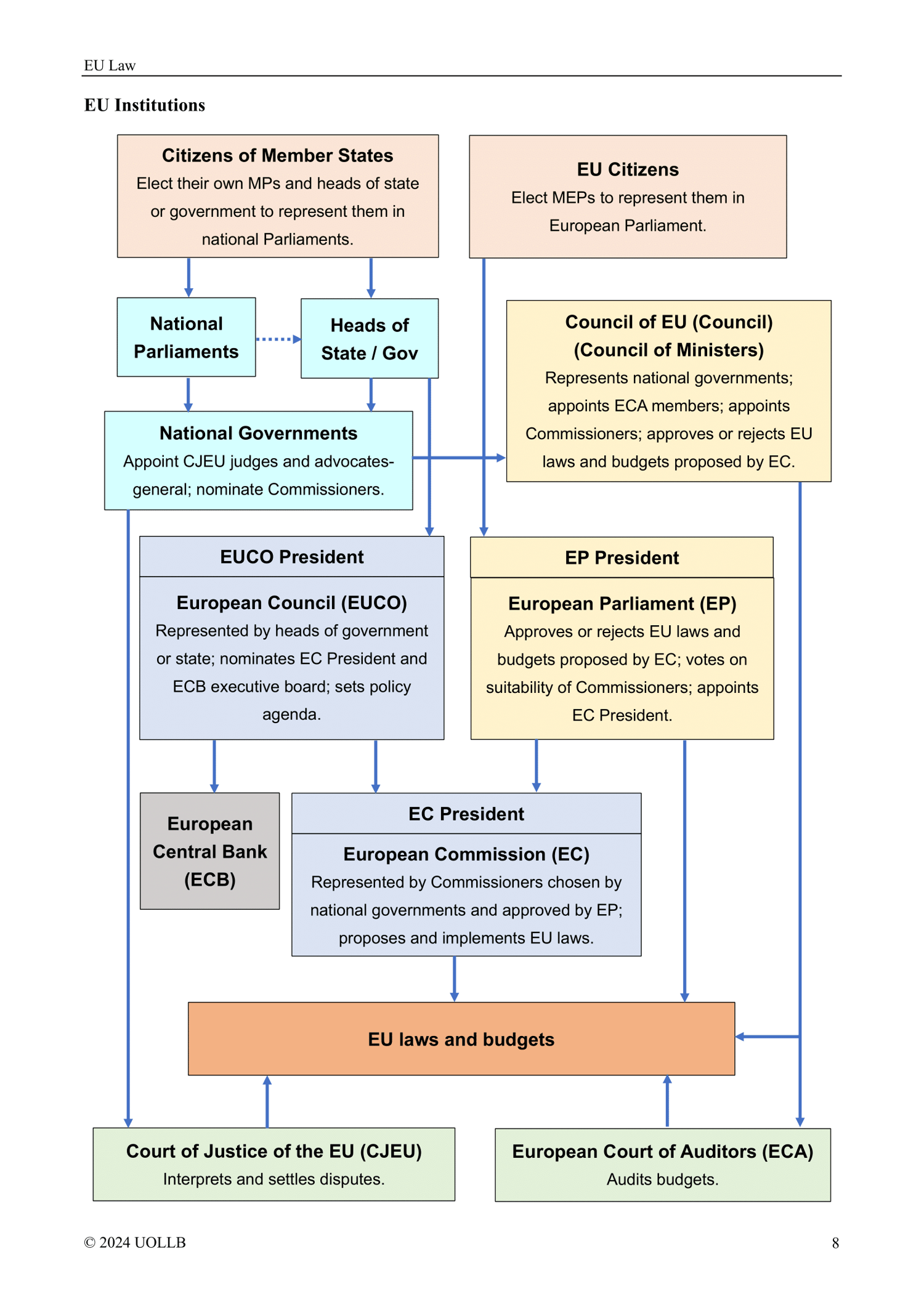

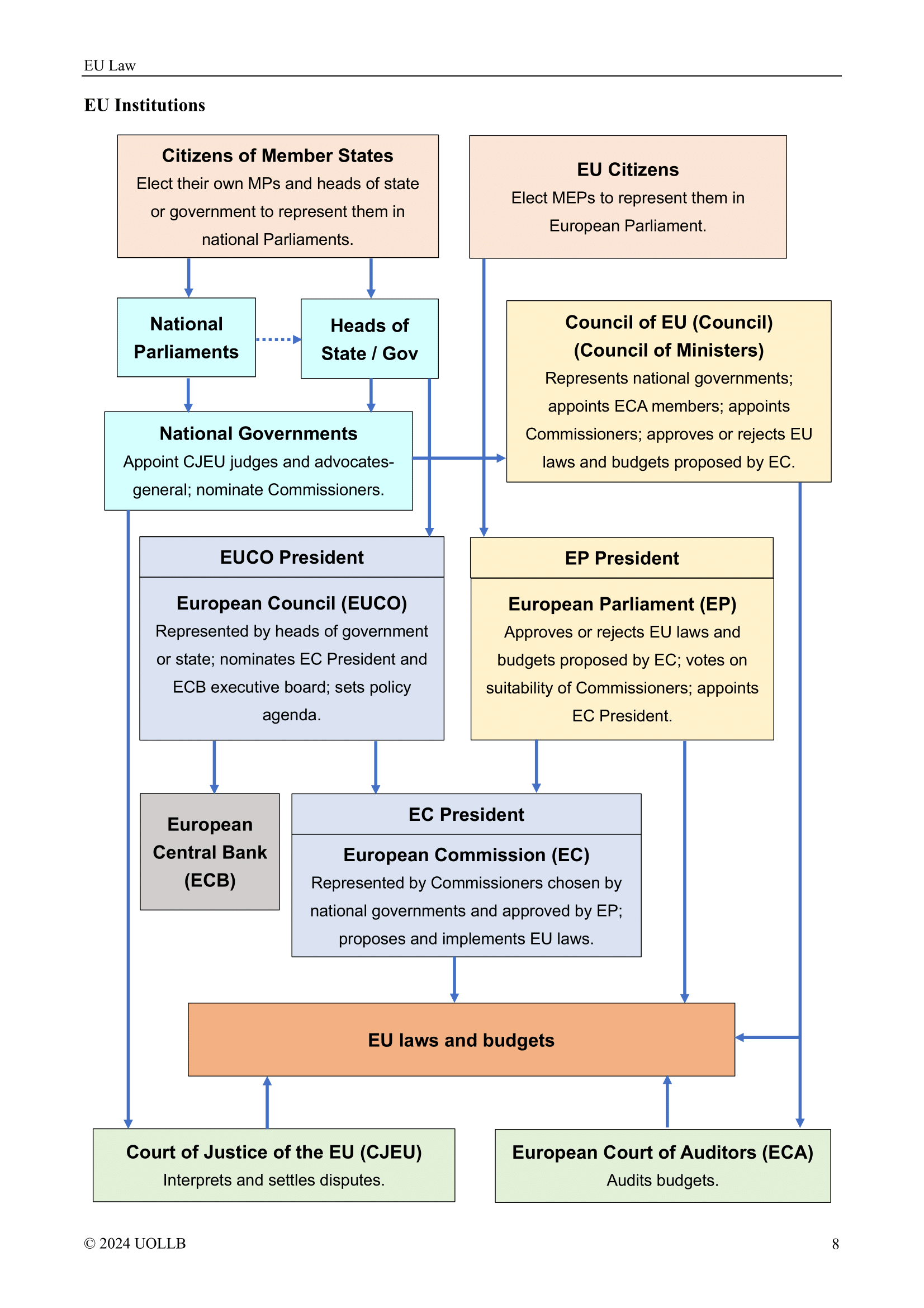

Present Structure of the EU: The current structure of the EU is defined by the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The TEU sets out the overall objectives, principles, and decision-making processes of the EU, while the TFEU focuses on specific policies and areas of competence. The EU is composed of several key institutions, including the European Commission (executive body), the European Council (consisting of heads of state or government), the European Parliament (representing EU citizens), the Council of the European Union (representing member states), the Court of Justice of the European Union (ensuring the interpretation and application of EU law), and the European Central Bank (responsible for the euro and monetary policy).

Characteristics of the EU Treaties: The EU treaties possess several characteristics that define the nature of the EU integration:

- Supranationalism: The EU treaties establish a supranational framework wherein the EU institutions have powers that go beyond those of individual member states. They can adopt binding decisions and regulations that are directly applicable to member states.

- Pooling of sovereignty: Member states voluntarily delegate certain powers to EU institutions, enabling collective decision-making and joint action in areas of common interest.

- Legal primacy: EU law takes precedence over national law. Member states are obliged to ensure compatibility between their national legislation and EU law.

- Dynamic process: The EU treaties provide a mechanism for further integration and adaptation to changing circumstances. Amendments can be made through treaty revisions or new treaties.

The Brexit Negotiations: The Brexit negotiations refer to the process by which the United Kingdom (UK) decided to leave the EU after the Brexit referendum held in June 2016. The UK formally triggered Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union in March 2017, initiating a two-year negotiation period to reach a withdrawal agreement. The negotiations involved discussions on various aspects, including the future relationship between the UK and the EU, such as trade, security, and citizen rights. The negotiations were complex and challenging, with key issues including the UK's financial obligations to the EU, the Irish border, and the status of EU citizens in the UK and UK citizens in the EU. The negotiations resulted in the signing of the Withdrawal Agreement between the UK and the EU in November 2018. The agreement outlined the terms of the UK's departure from the EU, including a transition period during which the UK would continue to follow EU rules while the future relationship was negotiated. The transition period lasted until December 31, 2020, during which the UK and the EU aimed to negotiate a comprehensive trade agreement. After several rounds of negotiations, the UK and the EU reached an agreement known as the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) on December 24, 2020. The TCA sets out the terms for trade, cooperation, and various other aspects of the future relationship between the UK and the EU. The Brexit negotiations were significant not only for the UK and the EU but also for the future of European integration. It marked the first time a member state chose to leave the EU, raising questions about the future of the Union and the impact on other member states. The negotiations highlighted the complexities of untangling a member state from the EU and establishing a new framework for cooperation. The Brexit process had political, economic, and social implications. It led to changes in trade relations, border controls, and the status of EU citizens residing in the UK and UK citizens residing in the EU. The negotiations also brought to the forefront discussions on sovereignty, national identity, and the future direction of the EU.

The Institutions of the EU: EU institutions play crucial roles in the decision-making, implementation, and governance of the EU. The main institutions are the European Council, the Council of Ministers, the European Commission, and the European Parliament. These institutions work together to ensure democratic decision-making, representation, and effective governance within the EU. They reflect the principles of supranationalism and the pooling of sovereignty among member states in order to promote European integration and address common challenges.

European Council: The European Council comprises the heads of state or government of its member states. It sets the overall political direction and priorities of the EU and provides guidance on major policy issues. The European Council meets several times a year to discuss and make decisions on various matters, such as economic coordination, foreign policy, and institutional reforms.

Council of Ministers: The Council of Ministers, also known as the Council of the European Union, represents the member states' governments and is responsible for adopting EU laws and coordinating policies. The Council consists of ministers from each member state, depending on the policy area under discussion. Its role is to negotiate and approve legislation proposed by the European Commission, along with setting the EU's common foreign and security policy.

European Commission: The European Commission is the executive body of the EU responsible for initiating legislation, implementing EU policies and decisions, managing the EU budget, and ensuring the enforcement of EU law. It is composed of commissioners, one from each member state, who are appointed by their respective governments and approved by the European Parliament. The Commission plays a crucial role in proposing new laws and regulations, overseeing the functioning of the EU's internal market, and representing the EU in international negotiations.

European Parliament: The European Parliament is the directly elected legislative body of the EU. Its members represent the citizens of the EU and are elected every five years. The Parliament shares legislative power with the Council of Ministers and has the authority to amend, reject, or adopt proposed legislation. It also scrutinises the work of the Commission and has the final say on the EU budget. The Parliament plays a significant role in shaping EU legislation and ensuring democratic accountability within the EU.

The Judicial Power of the EU: The judicial power of the EU is carried out by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and the General Court. These institutions play a crucial role in upholding the rule of law, ensuring the uniform interpretation and application of EU law, and resolving disputes within the EU. Their decisions contribute to the development of EU law and provide legal certainty for individuals, businesses, and governments operating within the EU. The independence and impartiality of these courts are essential for maintaining the integrity of the EU's judicial system and upholding the principles of justice and the rule of law throughout the EU.

The European Court of Justice (ECJ): The ECJ is the highest court in the EU and ensures the uniform interpretation and application of EU law. It consists of judges from each member state, appointed for renewable terms of six years. The ECJ has the authority to settle legal disputes between member states, EU institutions, and individuals or companies in areas such as competition law, fundamental rights, and the interpretation of EU treaties.

General Court: The General Court is a constituent court of the ECJ and specialises in handling direct actions brought by individuals, companies, and some organisations against EU institutions. It ensures judicial review of decisions made by the EU's administrative bodies. The General Court consists of judges appointed by mutual agreement between member states for renewable terms of six years. Its jurisdiction covers a wide range of areas, including competition law, state aid, trade, and intellectual property disputes.

EU Law Making and Sources of Laws: EU law making involves the creation of legal rules and regulations that are binding on member states. The primary sources of EU law are the treaties that serve as the foundation of the EU. The key treaties include the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). These treaties establish the EU's objectives, institutional framework, and allocation of powers. In addition to the treaties, secondary legislation is a vital source of EU law. Secondary legislation includes regulations, directives, decisions, and recommendations. Regulations are directly applicable and binding in their entirety in all member states, while directives are binding as to the result to be achieved but leave the choice of the form and methods to the member states.

Law-Making Procedures: The EU law-making procedures depend on the specific area and the legal instrument being used. The ordinary legislative procedure, also known as the co-decision procedure, is the most common procedure for adopting EU legislation. Under this procedure, the European Commission proposes legislation, and both the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union must agree on the final text before it becomes law. Other law-making procedures include the consultation procedure, where the Council consults the European Parliament on proposed legislation, and the consent procedure, where the European Parliament must give its consent for certain decisions, such as international agreements. The special legislative procedure applies to specific areas such as economic and monetary union, common foreign and security policy, and the accession of new member states.

Co-decision Procedure for Secondary Legislation: The co-decision procedure, also known as the ordinary legislative procedure, is the primary mechanism for adopting secondary legislation in the EU. It involves the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union sharing legislative power. The procedure begins with a proposal from the European Commission, followed by amendments and votes in both the Parliament and the Council. Both institutions must reach an agreement on the final text before it becomes law.

Regulations and Directives: Regulations and directives are two types of secondary legislation used in the EU. Regulations are directly applicable and binding in their entirety in all member states. Once adopted, they become law in all member states simultaneously without the need for national implementing measures. Directives, on the other hand, are binding as to the result to be achieved but leave the choice of form and methods to the member states. Member states must transpose directives into their national laws within a specified timeframe. This allows some flexibility in implementation while ensuring consistency in achieving the intended objectives across member states.

General Principles of Law: General principles of law play an important role in EU law. These principles are derived from the constitutional traditions and legal systems of member states, as well as from international agreements. They serve as fundamental principles guiding the interpretation and application of EU law. Examples of general principles include legal certainty, proportionality, fundamental rights, and non-discrimination. The Court of Justice of the European Union, particularly the European Court of Justice, has played a significant role in developing and interpreting these general principles, ensuring their consistent application and safeguarding the rule of law within the EU.

The Constitutional Principles of EU Law: The constitutional principles of EU law refer to the fundamental principles that underpin the legal framework of the EU. These principles are derived from the EU treaties and have been developed and interpreted by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) over time. Some key constitutional principles include the principle of conferral (EU can only act within the limits of the powers conferred upon it by member states), subsidiarity (EU acts only when it can achieve objectives better than member states individually), and proportionality (EU measures must not go beyond what is necessary to achieve the desired objectives).

Direct Effect: Direct effect is a principle of EU law that enables individuals to rely on EU law directly before national courts. It means that certain provisions of EU law, such as regulations, can create rights and obligations that individuals can enforce in national courts, even against the state or public authorities. Direct effect allows individuals to seek remedies for violations of their rights under EU law directly, without the need for national legislation to implement EU law first.

Indirect Effect: Indirect effect is another principle of EU law that requires national courts to interpret national law in a manner consistent with EU law. It applies when national legislation is ambiguous or incompatible with EU law. National courts are required to interpret national law in light of the relevant EU law provisions and to interpret national law as far as possible in a manner that achieves the objectives of EU law.

Supremacy of EU Law: The principle of the supremacy of EU law establishes that EU law takes precedence over national law in cases of conflict. This means that if there is a conflict between EU law and national law, EU law prevails. The principle of supremacy ensures the uniform application and interpretation of EU law across all member states. It was established by the CJEU in the landmark case of Costa v. ENEL, which held that EU law has a direct effect on member states and their national legal systems.

Doctrine of Consistent Interpretation: The doctrine of consistent interpretation is a principle developed by the CJEU to ensure the uniform application and interpretation of EU law by national courts. According to this doctrine, national courts must interpret national law in a manner that is consistent with the interpretation of the corresponding EU law provisions given by the CJEU. This principle aims to avoid divergent interpretations of EU law across member states and to ensure the effectiveness and uniformity of EU law throughout the EU.

State Liability: State liability refers to the legal principle that holds member states of the EU accountable for damages caused to individuals or businesses as a result of violations of EU law by the state or its authorities. The principle of state liability allows individuals to seek compensation for harm suffered due to the failure of a member state to fulfil its obligations under EU law. This principle aims to ensure that individuals are protected and compensated for any losses incurred as a result of the state's breach of EU law.

Free Movement of Goods: The free movement of goods is one of the fundamental principles of the EU internal market. It entails the removal of barriers to trade between member states, enabling the free movement of goods across national borders within the EU. The principle of free movement of goods prohibits any discriminatory measures or restrictions that may impede the import, export, or sale of goods within the EU.

Definition of Goods: In the context of EU law, goods refer to tangible and movable products, including both finished products and raw materials. The definition encompasses a wide range of items, such as machinery, vehicles, consumer products, agricultural products, and industrial materials. The concept of goods is crucial in determining the scope and application of EU rules and regulations relating to the free movement of goods.

Scope of Application: The scope of application of the free movement of goods principle extends to all goods traded within the EU internal market. It covers both goods produced within the EU and goods imported from non-EU countries. The principle applies to all member states and seeks to eliminate barriers to trade, such as customs duties, quantitative restrictions, discriminatory regulations, and unjustified technical barriers.

Quantitative Restrictions: Quantitative restrictions refer to measures imposed by member states that directly or indirectly limit the import, export, or sale of goods within the EU. These restrictions may take various forms, such as import quotas, export restrictions, product standards, labelling requirements, and licensing procedures. EU law prohibits member states from imposing quantitative restrictions on the free movement of goods unless they are justified by legitimate reasons such as public health, consumer protection, or the environment. Any restrictions imposed by member states must be proportionate and necessary to achieve the stated objectives, and they should not unduly hinder trade between member states.

Services and Establishment: Services and establishment are two key components of the EU internal market. The free movement of services allows service providers from one member state to offer their services in another member state without facing unjustified barriers or discrimination. Establishment, on the other hand, refers to the right of individuals and businesses to establish themselves in any member state to provide services on a stable and permanent basis.

Definition of Services: In the context of EU law, services encompass a wide range of economic activities that are not considered goods. The EU provides a broad definition of services, including activities such as banking and financial services, legal and accounting services, transportation services, tourism services, healthcare services, and various professional services. The definition is intentionally broad to cover a wide spectrum of economic activities in order to facilitate the free movement of services within the EU.

Definition of Establishment: Establishment refers to the right of individuals and businesses to set up and operate a commercial presence in a member state other than their home state. This can involve the establishment of branches, subsidiaries, agencies, or any other form of business presence. The concept of establishment allows businesses to expand their operations across borders and promotes cross-border investment and entrepreneurship within the EU.

Scope of Application: The free movement of services and establishment principles apply to all economic activities that fall within the definition of services, as defined by EU law. This includes both services provided by individuals and businesses, as well as those provided by public authorities. The scope of application extends to both domestic service providers and those from other member states seeking to provide services in another member state.

Quantitative Restrictions: Quantitative restrictions in the context of services and establishment refer to measures imposed by member states that limit or impede the provision of services or the establishment of businesses from other member states. Such restrictions can take various forms, including numerical quotas, authorisation requirements, discriminatory regulations, and unjustified administrative or financial burdens. EU law prohibits member states from imposing quantitative restrictions on the free movement of services and establishment, except in specific circumstances when they are justified by legitimate public interest reasons.

Definition of Measures Having Equivalent Effect: Measures having equivalent effect refer to any actions taken by member states that have a similar effect to quantitative restrictions on the free movement of goods within the EU. These measures may not take the form of traditional quantitative restrictions, such as quotas or import duties, but still have the effect of hindering or impeding the free movement of goods across national borders. The concept of measures having equivalent effect is crucial in assessing whether a member state's actions comply with the principles of the free movement of goods.

Distinctly and Indistinctly Applicable Measures: Distinctly applicable measures are those that specifically target goods from other member states, treating them less favourably than domestically produced goods. These measures are discriminatory and violate the principle of non-discrimination in the free movement of goods. On the other hand, indistinctly applicable measures are regulations that affect all goods, regardless of their origin, but may still have a potential impact on the free movement of goods. Indistinctly applicable measures can be permissible under certain conditions, provided they are justified by legitimate public interest objectives and are proportionate.

Derogations: Derogations, also known as exceptions or exemptions, are specific provisions that allow member states to deviate from the general principles of the free movement of goods in certain circumstances. These derogations are established in EU law and provide flexibility to member states to address legitimate public interest concerns. Derogations may be granted based on grounds such as public health, environmental protection, consumer safety, or cultural heritage. However, member states must ensure that any derogations they implement are justified, proportionate, and do not unduly restrict the free movement of goods.

Proportionality Test: The proportionality test is a legal principle used to assess the validity of measures that potentially restrict the free movement of goods. According to this principle, any measures implemented by member states that affect the free movement of goods must be proportionate to the objectives they seek to achieve. This means that the measures should be suitable and necessary to attain the desired goals, and they should not go beyond what is reasonably required. The proportionality test ensures that any restrictions on the free movement of goods are justified and balanced, considering both the interests of the member state and the principles of the EU's internal market.

Free Movement of Capital: The free movement of capital is a fundamental principle of the EU that allows for the unrestricted movement of capital between member states. It ensures that individuals, businesses, and financial institutions can invest, transfer, and trade capital, such as money, securities, and other financial assets, across national borders within the EU. The free movement of capital aims to create a single market for capital, promote economic integration, and foster investment and economic growth.

Definition of Capital: In EU law, capital refers to financial assets and resources, both tangible and intangible, which have economic value and can be used for investment or other economic purposes. It includes money, stocks, bonds, real estate, intellectual property rights, and other financial instruments. The definition of capital is broad and encompasses various forms of assets and investments.

Scope of Application: The free movement of capital applies to all movements of capital within the EU, whether they involve individuals, businesses, or financial institutions. It covers both direct investments, such as the acquisition of shares in companies or the establishment of branches and subsidiaries, and indirect investments, such as portfolio investments and financial transactions. The principle of free movement of capital applies to all member states of the EU.

Access to Market: The free movement of capital ensures that individuals, businesses, and financial institutions have access to the financial markets and investment opportunities in other member states. It eliminates restrictions and discriminatory measures that could hinder or limit the flow of capital between member states. The principle allows investors to seek the most favourable investment opportunities and financial services across the EU, contributing to market efficiency and competition.

Application to Third Countries: While the free movement of capital primarily applies to movements of capital within the EU, it also has implications for dealings with third countries (non-EU countries). The EU seeks to promote the liberalisation of capital flows with third countries through various agreements and arrangements. These aim to facilitate investments, protect investors' rights, and foster cooperation in the financial sector. However, the EU can also impose restrictions on capital flows with third countries for reasons such as national security or financial stability.

Derogations: Derogations provide exceptions or limitations to the general principle of the free movement of capital. Member states may derogate from the principle in specific circumstances, such as for prudential reasons, protection of public order, or safeguarding essential national interests. Derogations must be justified and proportionate to the legitimate objectives pursued and should not go beyond what is necessary to achieve those objectives.

Proportionality Test: The proportionality test is a legal principle used to assess whether measures restricting the free movement of capital are proportionate to the objectives they seek to achieve. It ensures that any restrictions imposed by member states on the free movement of capital are justified, necessary, and do not go beyond what is required to achieve legitimate public interest objectives. The proportionality test balances the free movement of capital with other important considerations, such as financial stability, investor protection, and the integrity of the financial system.

Trade Harmonisation: Trade harmonisation refers to the process of aligning regulations, standards, and policies related to trade and economic activities among member states of the EU. It aims to create a common framework that eliminates barriers and facilitates the free movement of goods, services, capital, and persons within the internal market of the EU. Trade harmonisation involves developing common rules and regulations, ensuring mutual recognition of standards, and promoting convergence in areas such as product safety, technical regulations, intellectual property rights, and competition law.

Competence and Approximation: Competence and approximation refer to the distribution of powers and responsibilities between the EU and its member states in the process of harmonising trade and economic policies. The EU has exclusive competence in certain areas, meaning that only the EU can legislate and adopt binding measures. In other areas, the EU and member states share competence, and the EU can adopt legislation that sets minimum standards while allowing member states to go beyond those standards. Approximation refers to the process of aligning national laws and regulations with EU legislation to ensure a common and harmonised approach.

The Limits of EU Power: The EU's power is limited by the principle of conferral, which means that the EU can only act within the limits of the powers conferred upon it by member states in the EU treaties. The EU has a set of competences defined in the treaties, and it can only take action in areas explicitly assigned to it. Member states retain sovereignty in areas outside the EU's competence. Additionally, the EU's actions must respect the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality, ensuring that decisions are taken at the EU level only when necessary and that they do not exceed what is needed to achieve the EU's objectives.

Article 114: Article 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) is a legal provision that grants the EU the power to adopt measures for the approximation of laws, regulations, and administrative provisions of member states in order to establish and ensure the functioning of the internal market. It provides the legal basis for the harmonisation of trade-related rules and regulations in areas where divergences among member states may hinder the functioning of the internal market. Article 114 allows the EU to adopt binding legislation that sets common standards and rules for the internal market, with the aim of eliminating barriers to trade and promoting economic integration.

Competition Policy: Competition policy in the EU is a set of rules and principles aimed at ensuring fair competition and preventing anti-competitive practices within the internal market. The primary objective of EU competition policy is to promote consumer welfare, encourage innovation, and maintain a level playing field for businesses. It encompasses both antitrust rules (dealing with agreements, abuse of dominance, and mergers) and state aid control (monitoring government assistance to prevent distortions of competition).

The Notion of Agreement: Under EU competition law, the notion of agreement refers to any form of coordination or cooperation between undertakings (businesses) that may affect competition. An agreement can be formal or informal, written or verbal, and explicit or implicit. It includes any understanding, arrangement, or concerted practice between competitors or between companies at different levels of the supply chain that restricts competition, allocates markets, fixes prices, or shares sensitive business information.

Decisions by Association of Undertakings: Decisions by associations of undertakings refer to concerted actions or decisions taken by industry associations, trade unions, or other collective bodies representing businesses. These decisions can have anti-competitive effects by restricting competition, setting common rules, or coordinating the behaviour of their members. Such decisions can be subject to scrutiny under EU competition law, and if they harm competition and distort the internal market, they may be deemed illegal and result in penalties or remedies.

Concerted Practice: Concerted practices refer to a form of coordination between undertakings that falls short of a formal agreement but still involves a cooperative behaviour that influences market conduct. It can include exchanges of information, parallel behaviour, signalling, or any other form of communication that leads to a coordination of commercial actions. Concerted practices that have an appreciable effect on competition and restrict or distort competition within the internal market are prohibited under EU competition law.

Exemptions under Article 101(3): Article 101(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) allows for certain agreements or practices that would typically be considered anti-competitive to be exempted if they contribute to economic efficiency, benefit consumers, and do not eliminate competition. To qualify for exemption, the agreements or practices must fulfil specific criteria, such as generating technological progress, allowing consumers a fair share of the resulting benefits, and not imposing unnecessary restrictions on competition.

Enforcement and Regulation 1/2003: Regulation 1/2003 is an EU regulation that establishes the rules for the enforcement of EU competition law. It decentralises the enforcement powers by empowering national competition authorities of member states to apply EU competition rules alongside the European Commission. It allows national authorities to investigate and sanction infringements of EU competition law within their jurisdictions, while the European Commission retains its central role in coordinating enforcement and ensuring consistent application of competition rules across the EU.

The Notion of Dominance and Abuse under Article 102: Article 102 of the TFEU deals with the abuse of a dominant position by undertakings in the internal market. Dominance refers to a position of economic strength held by one or more undertakings, allowing them to behave independently of competition and exert significant market power. Abuse of dominance occurs when a dominant undertaking engages in practices that harm competition, such as imposing unfair prices, limiting production, excluding competitors, or engaging in discriminatory practices. Article 102 aims to prevent the abuse of market power and maintain effective competition within the EU.

Free Movement of Persons and Citizenship: The free movement of persons is one of the fundamental principles of the EU and is closely linked to EU citizenship. It allows EU citizens to move, reside, work, and study in any member state of the EU, subject to certain limitations and conditions. EU citizenship is an additional citizenship granted to individuals who are nationals of a member state, entitling them to enjoy the rights and freedoms established by EU law.

Definition of Workers: In the context of free movement of persons, the term "workers" refers to individuals who are employed or self-employed in an economic activity in a member state. The definition includes both wage earners and self-employed persons, covering a wide range of professions and occupations. It encompasses full-time and part-time workers, as well as temporary workers and posted workers who are sent to work in another member state by their employer.

Scope of Application: The free movement of persons and citizenship rights apply to all EU citizens who exercise their right to move and reside in another member state. It covers various aspects, such as the right to enter and leave member states, the right to reside, work, and study, and access to social benefits and services. However, certain restrictions and limitations can be imposed in the interest of public policy, public security, and public health.

Principle of Non-Discrimination on Grounds of Nationality Derogations: The principle of non-discrimination on grounds of nationality is a fundamental principle of EU law. It prohibits discrimination based on nationality and ensures equal treatment for EU citizens in relation to the exercise of their free movement rights. However, member states can derogate from this principle under certain circumstances, such as for reasons of public policy, public security, or public health. Derogations must be justified, proportionate, and non-discriminatory.

Proportionality Test: The proportionality test is a legal principle used to assess whether measures restricting free movement rights are proportionate to the objectives they seek to achieve. It ensures that any restrictions imposed by member states on the free movement of persons are justified, necessary, and do not go beyond what is required to safeguard public policy, public security, or public health. The test balances the rights of free movement with the legitimate interests of member states.

Emergence of Concept of Citizenship: The concept of EU citizenship emerged with the adoption of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. It created a new legal status of EU citizenship alongside national citizenship. EU citizenship provides additional rights and protections to individuals who are nationals of a member state. These rights include the right to move and reside freely within the EU, the right to vote and stand as a candidate in European Parliament and local elections, the right to diplomatic and consular protection, and the right to petition the European Parliament and submit complaints to the European Ombudsman.

Scope of Application - Articles 20 and 21: Articles 20 and 21 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) define the scope of application of EU citizenship. Article 20 establishes the principle that EU citizenship is additional to national citizenship and does not replace it. It ensures that EU citizens enjoy the rights and protections established by EU law. Article 21 guarantees the right of every EU citizen to move and reside freely within the territory of the member states, subject to the limitations and conditions set out in EU law.

EU Human Rights: The EU is committed to upholding and promoting human rights within its member states. EU human rights encompass a broad range of fundamental rights and freedoms, including civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights. These rights are based on the principles of human dignity, equality, and the rule of law. The EU's human rights framework is guided by international human rights instruments, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights, as well as its own legal instruments.

Human Rights as General Principles of Law: Human rights are considered general principles of law within the EU legal framework. They form an integral part of EU law and are recognised and protected as fundamental rights. Human rights provide a foundation for the interpretation and application of EU law, ensuring that all EU actions and legislation are in line with the principles of human rights.

The Charter of Fundamental Rights: The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union is a legally binding document that sets out the fundamental rights and freedoms recognised within the EU. It was proclaimed in 2000 and became legally binding with the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009. The Charter covers a wide range of rights, including the right to life, liberty, and security, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and association, non-discrimination, privacy, and the right to a fair trial.

Scope of Application: The Charter of Fundamental Rights applies to the actions of the EU institutions and bodies when they are implementing EU law. It also applies to the member states when they are implementing EU law or acting within the scope of EU law. Additionally, national laws and practices must be interpreted and applied in line with the Charter. However, the Charter does not extend the competences of the EU beyond those conferred upon it by the member states in the EU treaties.

The Role of the European Court of Justice: The European Court of Justice (ECJ) plays a crucial role in safeguarding and interpreting EU human rights. It is the highest court of the EU and has the authority to ensure the uniform interpretation and application of EU law, including the Charter of Fundamental Rights. The ECJ is responsible for reviewing the legality of EU acts, ensuring compliance with EU human rights standards, and providing guidance on the interpretation of human rights principles in EU law. Individuals, as well as national courts and tribunals, can bring cases before the ECJ to seek remedies for alleged violations of their human rights under EU law.

The study of EU Law involves understanding the legal framework, principles, and institutions of the EU, as well as the interplay between EU law and national laws within the member states. EU law itself is a dynamic and evolving field that plays a significant role in shaping the legal landscape of Europe.

You can learn more about each topic and relevant case law with our exam-focused EU Law notes.